Coming Soon

Join the Direct Democracy Global Network

How Voters Build Direct Democracy

(Video)

Swiss Roots of the Network

Centuries ago, Alpine dwellers invented Switzerland's Direct Democracy according Swiss citizens political sovereignty.

Geneva's Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote treatises in the 18th century prescribing conditions for exercising political sovereignty -- and preserving it.

Purpose of the Network

Empowering voters worldwide to exercise their historical political sovereignty, and determine who runs for office, who gets elected, and what laws are passed.

PROFILE

Building Consensus

Setting Legislative Agendas

Forming Voting Blocs

Merging Blocs and Parties

Forming Electoral Coalitions

Nominating Electoral Candidates

Raising Campaign Funds

Electing Lawmakers

Launching Initiatives

Conducting Referendums

Mandating Legislation

Implementing Legislative Agendas

VOTERS TOWN HALL

I Financial Security and Basic Needs

II Health, Education, and Social Services

III Economic Systems, Labor, and Commerce

IV Governance, Rights, and Justice

V Environment, Infrastructure, and Resources

VI Security, Technology, and Global Affairs

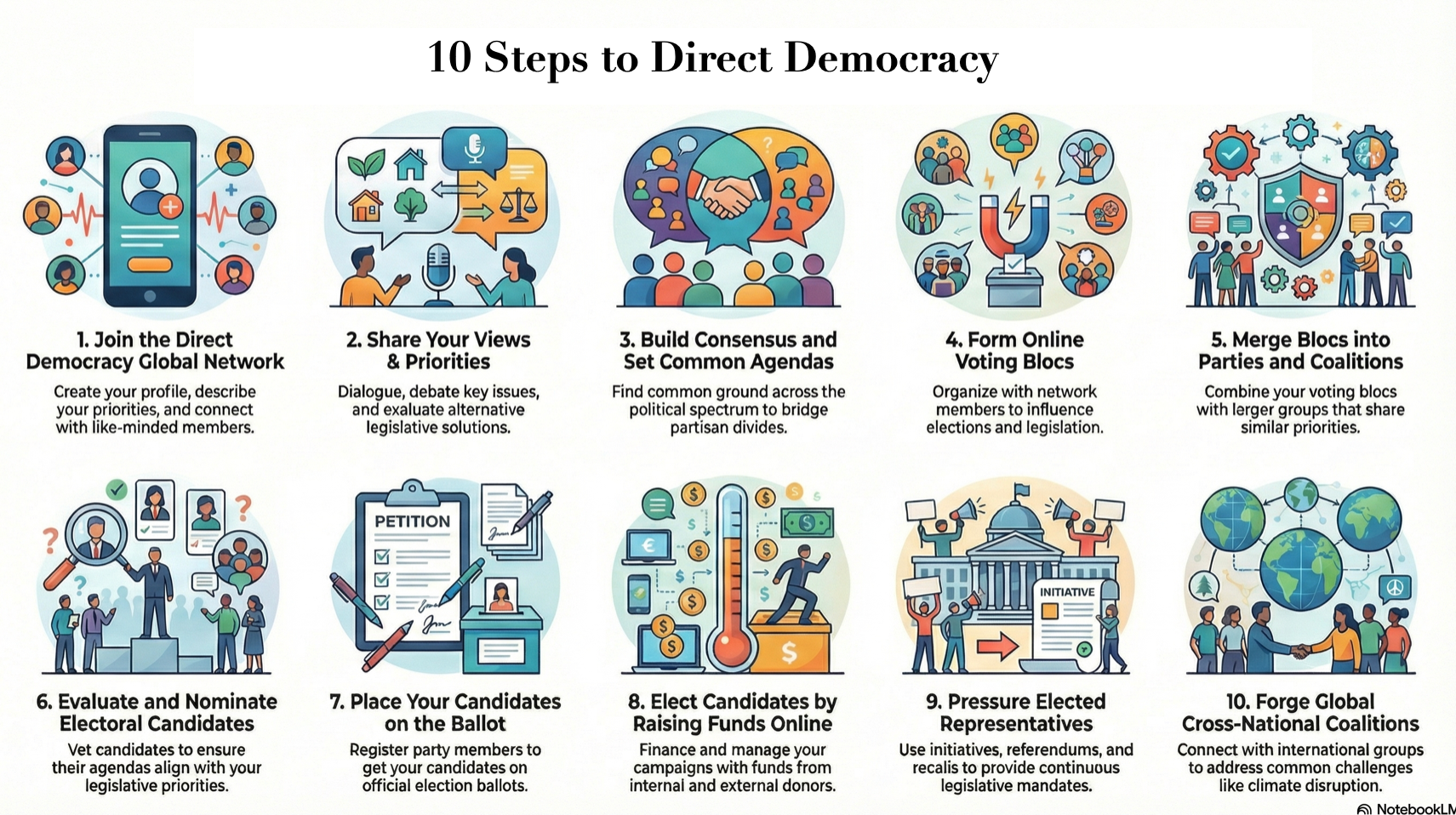

The steps below describe how voters worldwide will be able to use historic Swiss direct democracy practices when the network is fully operational.

.png)

Step 1. Join the Direct Democracy Global Network

Welcome to the network! You can join free of charge by creating your home page and profile by entering your sign-in username and password.

As a network member, you can use its direct democracy information and messaging tools and services, free of charge, to connect to like-minded voters. You can define and share your priorities and legislative agendas, and collaborate to enact your agendas.

You can join forces to create online political parties, voting blocs, and electoral coalitions. You can build consensus across partisan lines to set common legislative agendas, bridge divides, and determine who runs for office, who gets elected, and what laws are passed.

Network services include conducting initiatives and referendums, as the Swiss have been doing for centuries. You can access to the network's Fact Checker and Voting Utility to cast votes on a variety of proposals.

Step 2. Share Your Views and Priorities

Express your views, define your priorities, and create your own legislative agendas.

Save your priorities and agendas, and share them selectively, privately, and confidentially with individuals and groups you choose. Below are four methods.

(1) Describe any number of priorities in your own words, and set your own legislative agendas.

(2) Search the network priorities database listing priorities from a range of sources, and access web links to information about them. Select those that are similar to your own priorities, and what you want to happen legislatively.

(3) View priorities and agendas of individual network members who agree to share them, and select those you prefer. Names are not provided.

(4) Choose your legislative priorities and agendas from those of political parties, voting blocs, and electoral coalitions hosted on the network that agree to share them.

Step 3. Build Consensus and Set Common Agendas

In addition to defining your own priorities and setting your own agendas, you can connect to other network members to set common legislative agendas including priorities you share.

You can actively participate in collective efforts to build consensus across partisanlines. You can conduct online dialogues and debates, and reconcile divergent perspectives and objectives.

During your participation, you can clarify the meaning of your priorities and show how they resemble and/or diverge from other participants’ priorities. You can use the network’s Fact Checker to distinguish facts from misinformation.

You and other network participants can decide, at any point in time, to update and vote online to determine which priorities to include in common legislative agendas, using the network’s Voting Utility.

Step 4. Form Online Voting Blocs

You can collaborate with like-minded network members who espouse legislative priorities similar to yours, to take advantage of the network’s political organizing tools.

You can transform your personal networks into voting blocs and host and co-manage them on the network. Together you can utilize the network’s direct democracy tools and services to carry out tasks that are vital to fully functioning democracies.

Your blocs can function uniquely online within the network, or operate outside the network in locations and forms chosen by the members. They can choose to join existing blocs, parties, and coalitions, online and offline, and/or opt to work independently.

Step 5. Merge Blocs into Parties and Coalitions

You can merge your voting blocs hosted on the network with political parties and coalitions also hosted on the network, so they can build consensus across partisan lines and increase numbers of voters in their electoral base.

You can also decide to form your own political parties and electoral coalitions.

They can be organized informally, and create temporary ad hoc alliances with other parties.

In addition, you can organize them formally and register them officially with local governmental election agencies, to enable them to fully participate in electoral processes throughout election cycles.

Since their members can freely define their priorities and set their legislative agendas without regard to doctrines or ideogies, they can function autonomously and adhere exclusively to the decisions of their members.

Step 6. Evaluate and Nominate Electoral Candidates

Thanks to the beneficial reversal of traditional practices, you and network voters can use the Direct Democracy Global Network to evaluate and nominate electoral candidates of your choice, rather than be limited to choosing among candidates already on the ballot.

You can collaborate with network members to identify and evaluate prospective candidates in depth, according to criteria of their choosing.

You can scrutinize candidates' prior activities, votes, and priorities to evaluate whether they align with your own priorities, and those of your voting blocs, political parties, and electoral coalitions.

In addition, you can conduct online interviews with prospective candidate, and evaluate first hand whether they appear likely to be consensus-builders if elected, and whether they will reach across partisan divides to prevent stalemates.

Step 7. Place Your Candidates on the Ballot

Laws, rules, and regulations for placing candidates on election ballots vary widely. They can be quite cumbersome, and require close and continuous scrutiny.

These complications can result from deliberate efforts to obstruct competitive electoral races by keeping voters from having fair chances to elect candidates of their choice.

Fortunately, there will be large numbers of election experts who are members of the Direct Democracy Global Network who will share their expertise with you and other members to ensure free and fair elections.

One of the most important steps is plan ning ahead and constantly monitoring changes in official election laws, regulations, procedures, to ensure you and network members, and your voting blocs, political parties, and electoral coalitions, are able to get your candidates' names on official primary ballots.

Step 8. Elect Candidates by Raising Funds Online

A strategically important key to winning elections is to raise funds to finance your campaigns that enable you to reach out to as many voters as you can. You can seek funding from sources inside and outside the network.

Billions of dollars are raised and spent during every election cycle. There are a variety of channels of communication that you can use to direct such funds to your campaigns.

The success of your fundraising efforts might be facilitated if prospective donors are informed of your membership in the Direct Democracy Global Network.

Increasing numbers of politically engaged individuals, groups, and organizations are devoting their time, energy, and donations to strengthening and re-invigorating democratic electoral and legislative processes and institutions.

Step 9. Pressure Elected Representatives

You and the network members of your political parties, voting blocs, and electoral coalitions can actively participate in post-election decision-making in all branches of government, by using direct democracy tools provided by the network.

You can conduct petition drives, referendums, initiatives, and recall votes, publicize the results, and use them to transmit written mandates to decision-makers during all phases of governmental decision-making processes.

These mandates will reflect the needs and demands of the public and their constituents during all phases of post-election decision-making.

Your capabilities and those of network members to determine the outcomes of past and future elections will prompt decision-makers to heed your demands.

Step 10. Forge Cross-National Coalitions

You can join with network members to design and implement life-preserving policies and plans, such as curbing climate disruption, and collectively devising common peace-making plans worldwide.

By connecting online with network members and voters where you live, as well as across nation-state frontiers, you can collaborate to design and enact peace-making plans to resolve confrontations and conflicts worldwide. Voters living in different countries often experience similar needs, crises, and emergencies, even though their governments may tend to disagree.

You can use the network to connect to voters with experiences similar to yours. Network tools enable you to collectively create online political parties, voting blocs, and electoral coalitions dedicated to peace-making.

You can use network agenda-setting, political organizing, and electoral tools to create common fronts to induce lawmakers to enact common peace-making plans, within and across frontiers.

Resources

Lewis Waller. 2023. How Switzerland Changed the World. YouTube.

Clay Shirky. 2008. Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing Without Organizations. Penguin Group. Wikipedia.

Beau Sievers, et.al. 2022. How Consensus-Building Conversation Changes Our Minds and Aligns Our Brains. Europe PMC. September 17, 2022.

Peter Russell. The Global Brain. Wikipedia.

Dacher Keltner. 2015. Survival of the Kindest - YouTube. University of California/Berkeley.

Contact

Copyright 2026 Direct Democracy Global Network

All Rights Reserved